Lauri recounts her biking experience in Colombia and explains why it is earning its place in the front of the bicycle movement with its visionary bicycle legislation.

How does Colombia, one of the most notoriously happiest countries in the world, intend to make its 49 million residents even happier? It passes landmark legislation designed to make bicycling its country’s primary means of transportation.

Yes, that is right, Colombia does not just want to make bicycling an acceptable form of transportation, but it wants to make bicycling the country’s primary source of transportation. Further, it has a plan and legislative mandates in place to achieve its ambitious mission.

Law 1811 of 2016

In October of 2016, the Colombian Legislature enacted Law 1811 of 2016: An Act to Grant Incentives to Promote the Use of the Bicycle Throughout the Country and to Modify the National Transit Code. The law, among other things, explicitly acknowledges the negative impacts of motorized vehicles on the environment and seeks to get more people on bikes by offering them workplace and other incentives. It also prioritizes the development of integrated transportation systems and mandates the inclusion of bicycle infrastructure within those systems. In addition, the law modifies Colombia’s National Transit Code to give bicycle riders important rights on the roadway, as well as to require and encourage cooperation from law enforcement, educational institutions, transit operators, local governments, national ministries and others to ensure that people are aware of, honor and enforce those rights.

Highlights

Among the legislation’s most popular provisions is Article 5, the “biking to work = paid vacation” provision, which incentivizes public workers to ride their bicycles to work regularly by giving them up to eight free paid half days off work annually for every thirty commutes to work by bicycle.

Also noteworthy is Article 6, which requires parking areas serving public buildings to ensure that at least ten percent of parking spaces in those areas be reserved for bicycles.

The 2016 legislation also contains several provisions that encourage the use of bicycles within integrated transportation systems. Among them is the provision that requires transit operators to give one free transit pass to bicycle riders who show proof of thirty proofs of bicycle uses. There is also the provision that requires metro and tram systems to develop a protocol to allow bicycle riders to bring their bicycles on board and/or to provide compartments for bicycle transport.

In addition, and important for transportation planners and others, are the provisions in the new law that encourage the collection and analysis of sustainable transportation data. Areas of 100,000 or more inhabitants are required to develop information systems designed to collect data about the current use of and projection of future demand for non-motor vehicles, as well as a system for recording complaints, questions, and requests associated with non-motorized transportation.

Further, Law 1811 amends Colombia’s National Transit Code to prioritize bicycles and promote a culture of safety and respect on the roadway for all traffic, including bicycle traffic. Among other things, the law: restates the obligations of Colombia’s educational institutions to offer programming promoting bicycle use and sustainable mobility; requires the Colombia’s Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Tourism to carry out a program promoting the production and acquisition of bicycles throughout the country; amends a 2011 provision in the Transit Code to now state that education in road safety is a matter of public interest and should be the subject of debate among the citizens; obligates local governments to promote and support training, information campaigns, research and development on road safety and sustainable mobility; and mandates changes to Colombia’s National Road Safety Plan to incentivize and encourage the responsible and respectful use of bicycles as a means of transport in the country.

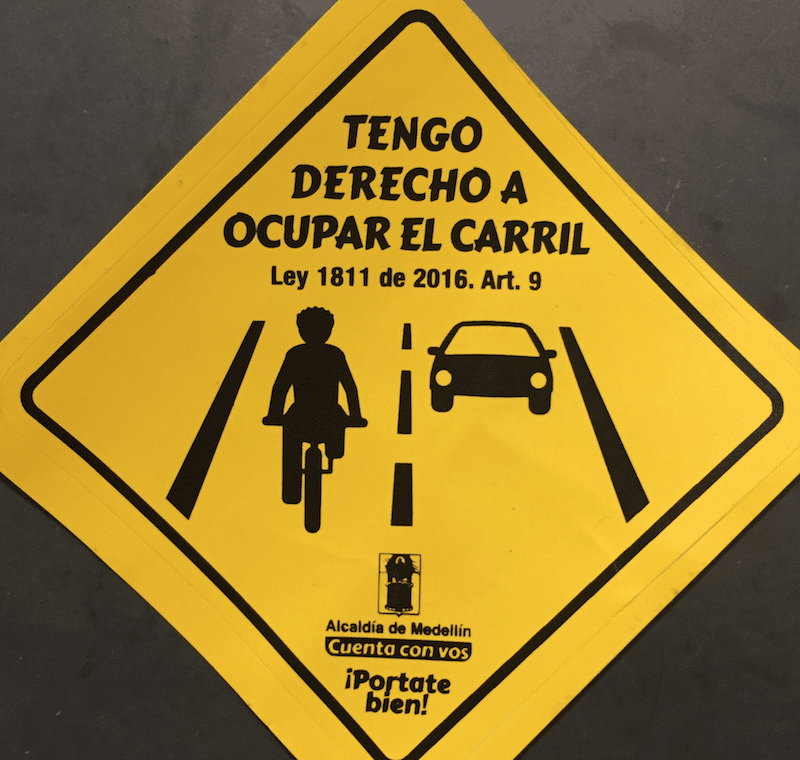

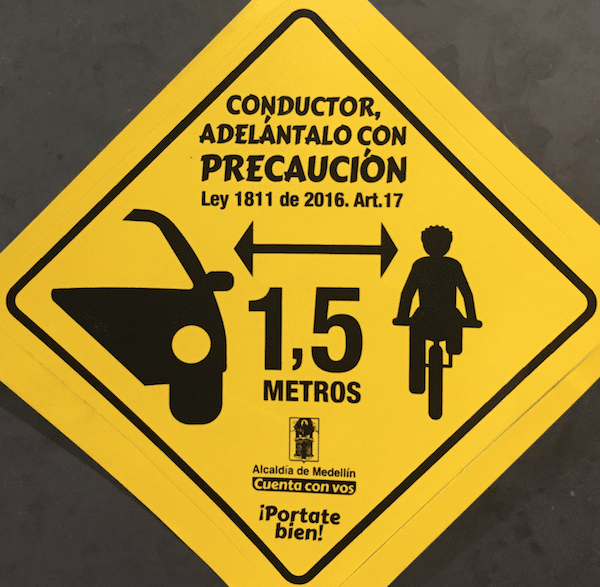

Likewise, the 2016 legislation amends 2002 legislation to require drivers of motor vehicles to: give priority and respect the rights of bicycle riders and pedestrians; prohibit the parking of motorized vehicles in bicycle paths, dedicated cycling lanes or other places where bicycles have priority; and require that 1.5 meters (nearly five feet) be given by motor vehicles when passing bicycle riders.

Time for Implementation

Despite Law 1811’s promise, it is clearly still in its infancy. Not only do most of the provisions in the law currently lack teeth, they lack even baby teeth. Most of the 2016 legislation’s provisions are designed to give those responsible for providing incentives or making changes to infrastructure sufficient time to carry out the law’s mandates. For example, individual transportation districts and municipalities are not obligated to provide a free transit pass to persons providing proof of thirty bicycle commutes until specific triggering events, such as the renegotiation of an operating contract within that district or municipality. Likewise, the bicycle parking requirements discussed above do not become enforceable until October of 2018.

It is also noteworthy that some of the provisions found in the legislation are more suggestive than regulatory. For example, there is language in Article 5 suggesting that private employers offer the same “biking to work = paid vacation” incentive offered by public employers, but nothing in the law requiring them to implement such an incentive program. Similarly, some of the legislation contains mandates that need only be fulfilled depending on available resources, leaving room for debate regarding whether a district or an entity must carry out the same. For example, Article 7, which provides for the development of information systems to collect data on non-motorized transportation usage and demands, contains such a provision. As such, it is difficult to gauge whether these provisions will be implemented in the future.

Still, Law 1811 of 2016 legislation demonstrates true foresight on the part of the Colombian Legislature and its constituents, and it has real potential to meet its intended purposes. This is particularly so given that significant numbers of private, public and nonprofit entities and Colombian residents from different social strata appear to be on board with Colombia’s bicycle movement.

Snapshots from Medellín

As a recent guest in Medellín, Colombia’s second largest city, there were signs everywhere foreshadowing Law 1811’s likelihood of success, including: (1) the existence of expansive bicycle infrastructure, (2) the implementation of law enforcement efforts to protect the rights of bicycle riders, (3) the presence of integrated transportation systems, (4) the promulgation of bicycling education and awareness initiatives, (5) the inclusion of bicycling in popular culture, (6) efforts by the private sector to encourage bicycling, and (7) the rise of bicycle tourism. Each is elaborated on below. It should be noted, however, that Medellín is an exceptional city—one that has already earned a reputation as “a miracle of reinvention” for its ability to turn what was once a forbidden city into a model city. As such, while Medellín may be a harbinger of what we can expect from other parts of Colombia in the future, the bicycle infrastructure and the bicycle friendly culture seen in Medellín are not necessarily representative of what is taking place throughout Colombia. But see, Improving life in Bogota by empowering citizens to cycle (suggesting that what is taking place in Medellín is also taking place in other Colombian cities). Further, the observations about Medellín are just that—observations. They are snapshots from the perspective of a short-term visitor to the city. They have been harvested and are being shared in hopes that others will take an interest in Medellín’s bicycle initiatives and get involved in supporting, studying and spreading their efficacy and impact.

The Existence Expansive Bicycle Infrastructure in Columbia

Perhaps one of the most noticeable signs throughout Medellín of Law 1811’s potential for success is the already ever-so-present bicycle infrastructure. Medellín began investing in its bicycle infrastructure around the turn of the century, already has an extensive bicycle path system in place, and has plans to build several hundred kilometers more bicycle paths in the future. See Medellín Ministry of Mobility Website; see also How Medellin is Making the Most of Investment and Infrastructure; and see Cycling In the City of Eternal Spring – Medellín, Colombia.

Bicycle paths like the ones shown in the photo above run alongside the city’s major arteries, are accessible, and take riders to Medellín’s city center, universities, parks, green lungs, library parks and tourist destinations. They are found everywhere from Medellín’s wealthy neighborhoods to the poorest and most remote sections of the city. Further, the bike paths are being used and already appear to be changing transportation culture. Per Medellín’s Ministry of Mobility, approximately 50,000 trips a day are taken by bike, many of which are attributed to the existence of bicycle paths.

Protected intersections, such as the one shown below, are also commonplace in Medellín.

Unlike in the United States, where protected intersections are a rarity and make headlines each time they are installed, in Medellín, protected intersections are truly ubiquitous. This infrastructure not only makes it easy for people to get around by bicycle and foot, but it signals true respect for the safety of all users of Medellín’s public ways. Further, the presence of protected intersections throughout the city regularly reinforces the message that all forms of traffic matter and that public ways belong to all users, not just motor vehicles.

The Implementation of Law Enforcement Efforts

Law enforcement efforts relating to Law 1811 of 2016 also appear to be partially underway in Medellín. During an early morning run through the Laureles District of the city, I encountered the transit employees shown below watching over a bicycle path.

When I asked them what they were doing, they told me that they were doing their rush hour policing of Medellín’s bicycle paths to ensure that motorcycles, taxis, delivery trucks and other motor vehicles did not use or in any way inhibit the flow of bicycle traffic on the same in violation of the Transit Code discussed above. Interestingly, the transit employees also shared that they were directed to prioritize warnings and citations to motor vehicle operators placing bicyclists at risk, as opposed to ticketing bad bicycle rider behavior. It was noted that enforcement of the laws governing bicycle rider behavior was also important, but that the government’s number one priority was to encourage the use of bicycling infrastructure by making it safe and accessible for its users.

While not based on any hard data, my observation and experience in Medellín was that law enforcement officers were also not yet focused on enforcement of the 1.5 meters law and other laws designed to protect bicyclists in the roadway. It was very common to see large buses and trucks passing and riding alongside bicycle riders with less than a foot to spare. That said, because of the number of bicycles, motorcycles, and scooters on Medellín’s roadways, drivers appeared to be generally more cognizant of bicycles on the roadway and had a better appreciation of their speed and place in the flow of traffic. Again, without any hard data to go by, I would suspect that right hooks and improper turns in front of bicycle riders are less common in Medellín than they are in New York, as drivers of automobiles, buses, and trucks seem to expect and generally respect two-wheeled traffic.

The Presence of Integrated Transportation Systems

Medellín also appears to be already well on its way to meeting the integrated transportation system mandates of Law No. 1811.

Public bike share stations, which are maintained and operated by EnCicla, are not only found throughout the city but are being heavily used by a wide range of people. EnCicla bikes are free to registered users, which adds to the bike share system’s popularity. The system is used by well-heeled professionals, uniformed service workers, university students and others. Further, as shown in this map, the EnCicla stations are strategically placed near metro, bus and tram stations and city centers, so that users can easily switch from one mode of transportation to another to make their ways across the city. Efforts are also being made to link the EnCicla registration system with the mass transportation system registration system so that ultimately users can have one card that accesses all integrated transportation systems. See La Cívica and EnCicla join forces in the Integrated Transportation System. Likewise, EnCicla offers an app that allows users to find, access and determine the availability of EnCicla bicycles throughout the city. See EnCicla: From a Student Project to 38,000 a Day Daily Users. In addition, public announcements are made on the metro about the EnCicla stations and encouraging the use of bicycles and integrated transportation systems.

Locals also report that efforts are underway to allow people to bring their bicycles on the gondola lines shown below, which lead to and from some of Medellín’s poorest communities.

If the City’s already innovative public infrastructure system and commitment to providing all of its citizens with access to transportation, social and other services are any indications of how Medellín will tackle the integrated transportation system requirements of Law 1811, there is true hope for real urban mobility in Medellín and other Colombian cities.

Colombia Bicycling Education and Awareness Initiatives

Public, private and non-governmental entities within Medellín are already at work on public education and awareness initiatives surrounding bicycling, which are required by Law 1811. Among them is Medellín’s Ministry of Mobility, which offers information about bicycling commuting and an explanation of why the city is committed to sustainable transportation on its website. Inder, Medellín’s Institute of Sports and Recreation, also offers information about weekly bike rides and weekly bicycling classes for children.

Also noteworthy is Collective Corporation SiCLas, a non-profit organization that offers introductory, intermediate and advanced bicycling classes for people of all ages that wish to learn how to ride safely and respectfully on city streets.

Casa BiciRollings, a private bicycle shop that specializes in repairing and restoring vintage bicycles and making bicycling accessible to all populations, offers bicycle users maintenance and repair classes. Likewise, La Magia de la Bici, a newer entity in Medellín, offers educational cycling tours of Medellín to tourists, as well as also reports that it trains bus operators throughout Medellín on a safe operation near bicycle riders on public roadways and works on other social justice issues.

The Liga de Ciclismo de Antioquia, which has offices next to the City’s Velodrome is teaching bicycling racing and technical skills to people of all ages and provides access to bicycles and programming to school children. Shown below are youth riders at Medellín’s Velodrome.

These wide-ranging efforts, which clearly are directed at diverse populations living in, visiting and using the streets and public ways of Medellín, signal that the resources are already in place to build public capacity to appreciate, use, maintain and respect bicycles. In other words, in Medellín, the educational and public awareness mandates contained within Law 1811 are already well underway.

The Inclusion of Bicycling into Popular Culture

Another sign that Law 1811 will meet its intended goal of making bicycling the primary means of transportation for the country of Colombia is the growing love of the sport of bicycling, which has recently been fueled by the accomplishments of Colombia’s Mariana Pajón, Rigoberto Urán, and Nairo Quintana. See Mariana Pajón, la mejor deportista colombiana de todos los tiempos; see also From street vendor to Tour de France star, the extraordinary determination of Rigoberto Urán; Nairo Quintana revives cycling passion in Colombia. Unlike in the United States, where most people are unable to tell you who won the 2017 Tour de France, street vendors in one of Medellín’s poorest and most remote neighborhoods jokingly bestowed Chris Froome’s name on my husband as he beat us to the top of a hillside climb on the outskirts of the city.

Not only do significant numbers of Colombians follow international and national bicycle races, but many are active riders themselves. Colombians of all ages can regularly be found participating in weekly rides called “ciclovías,” which involve local municipalities shutting down public roadways to motorized vehicles so that bicycle riders, pedestrians, roller skaters and others can recreate in them. Ciclovías take place throughout the country and draw crowds of up to a million people, depending on the location. See How a Colombian Cycling Tradition Changed the World. In Medellín, ciclovías are held in various locations on Sundays and Tuesday and Thursday evenings and are sponsored by Inder, the local Sports and Recreation Institute. See Ciclovías Recreativas Institucional y Barriales. According to Jhon Jairo Escobar, who heads one of the ciclovía programs, there are times when more than 100,000 people in the greater Medellín participate in the weekly rides. See Ciclovía Gets Medellín Moving.

Similarly, turnouts for “SiCleadas,” critical mass type rides in Medellín carried out by Collective Corporation SiCLas, suggest that bicycling is becoming a part of popular culture in Medellín. These rides, which are designed to build community and create a public awareness surrounding bicyclists’ right to travel on city streets, draw thousands of people. The one we attended while in Medellín involved a ride where the approximately 3,000 attendees rode together for approximately 18 kilometers.

When thousands of bicycle riders from all walks of life show up to collectively claim the right to use public roadways and celebrate bicycling, it becomes possible to envision a future Colombia where bicycling is the primary means of transportation.

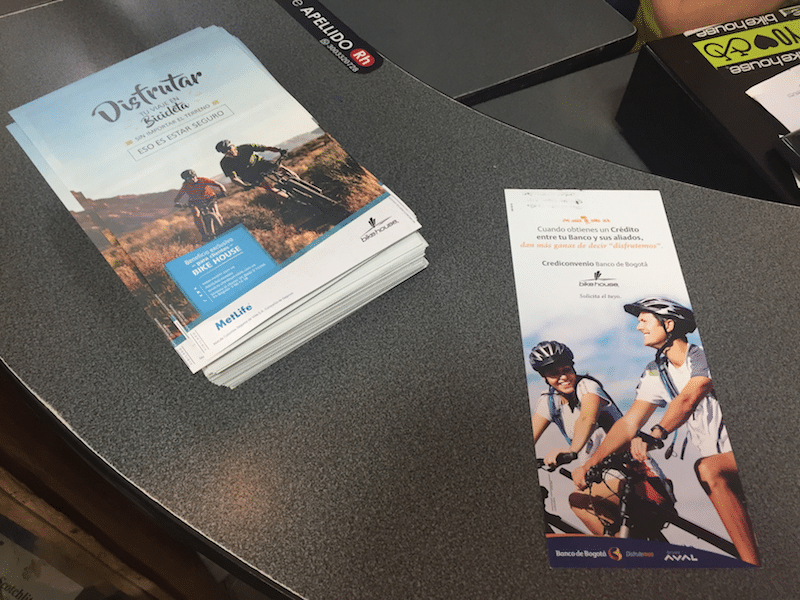

The Promotion of Bicycles by the Private Sector

Efforts by the private sector to get more people on bikes are also apparent in Medellín, which was a positive indication that the softer provisions of Law 1811, which encourage, but don’t require, private businesses to support the national government’s prioritization of the bicycle, were being taken seriously. While at Bike House, one of Medellín’s many bicycle shops, we saw pamphlets and flyers from various banks and insurance companies encouraging people to buy and use bikes by offering special financing and insurance for bike riders. In addition, shops that sell motorcycles and mopeds also sell and promote e-bikes, and financing arrangements for the purchase of e-bikes are also available.

The Rise of Colombia Bicycle Tourism

Finally, the rise of bicycle tourism in Medellín and other parts of Colombia appears to suggest that Law 1811 stands a chance of succeeding. See Colombia Just Might Be the Bucket-List Cycling Destination You’re Looking For; see also Cycling in the City of Eternal Spring. While the country does not yet appear to be overrun with bicyclist tourists, the international bicycling community is taking a keen interest in Colombia as a cycling destination, and it likely won’t be long before tourists are adding to the numbers of people looking for bicycling services and accommodations, including some of those provided for in Law 1811 of 2016. Further, once Colombians begin to realize the many economic benefits of bicycling tourism, there is a possibility that there will be even more positive cultural shifts within Colombian communities about how bicycle riders of all nationalities (including Colombians) are perceived, treated and accommodated on the roadway and within transportation systems.

Getting on Colombia’s Wheel

While only time will tell how the various provisions within Law 1811 of 2016 will play out, one thing is for sure—Colombia is making its way to the front of the bicycle movement peloton. The country’s commitment to using the bicycle as an agent for addressing social, environmental, health and transportation problems is not only visible, but it is impressive. Even if Colombia is not able to achieve everything it hopes to through its new legislation, if other countries can get on Colombia’s wheel, work from its momentum, adopt its “si se puede” attitude, and start taking similar pulls for the cause, the overall bicycling movement and our individual communities will be stronger, healthier and more sustainable places.

Lauri Boxer-Macomber has been an avid rider for decades. Lauri’s Maine law practice is focused on advocating for the rights of bicyclists, pedestrians, and other vulnerable road users.

Lauri’s riding experience and legal training are complemented by her advocacy work. She is an active Board Member of the Bicycle Coalition of Maine, a Governor of the Maine Trial Lawyers Association, and a Member of the American League of Bicyclists. She also chairs the Bicycle Coalition of Maine’s Policy and Legislation Committee and is one of the founding members and facilitators of the Bicycle Coalition of Maine’s Law Enforcement Collaborative, a group of law enforcement officers, planners, bicycle advocates, and others who meet regularly with the goal of improving safety on Maine’s roadways.