It's Passed the House. And on April 29th, It's Before the Oregon Senate

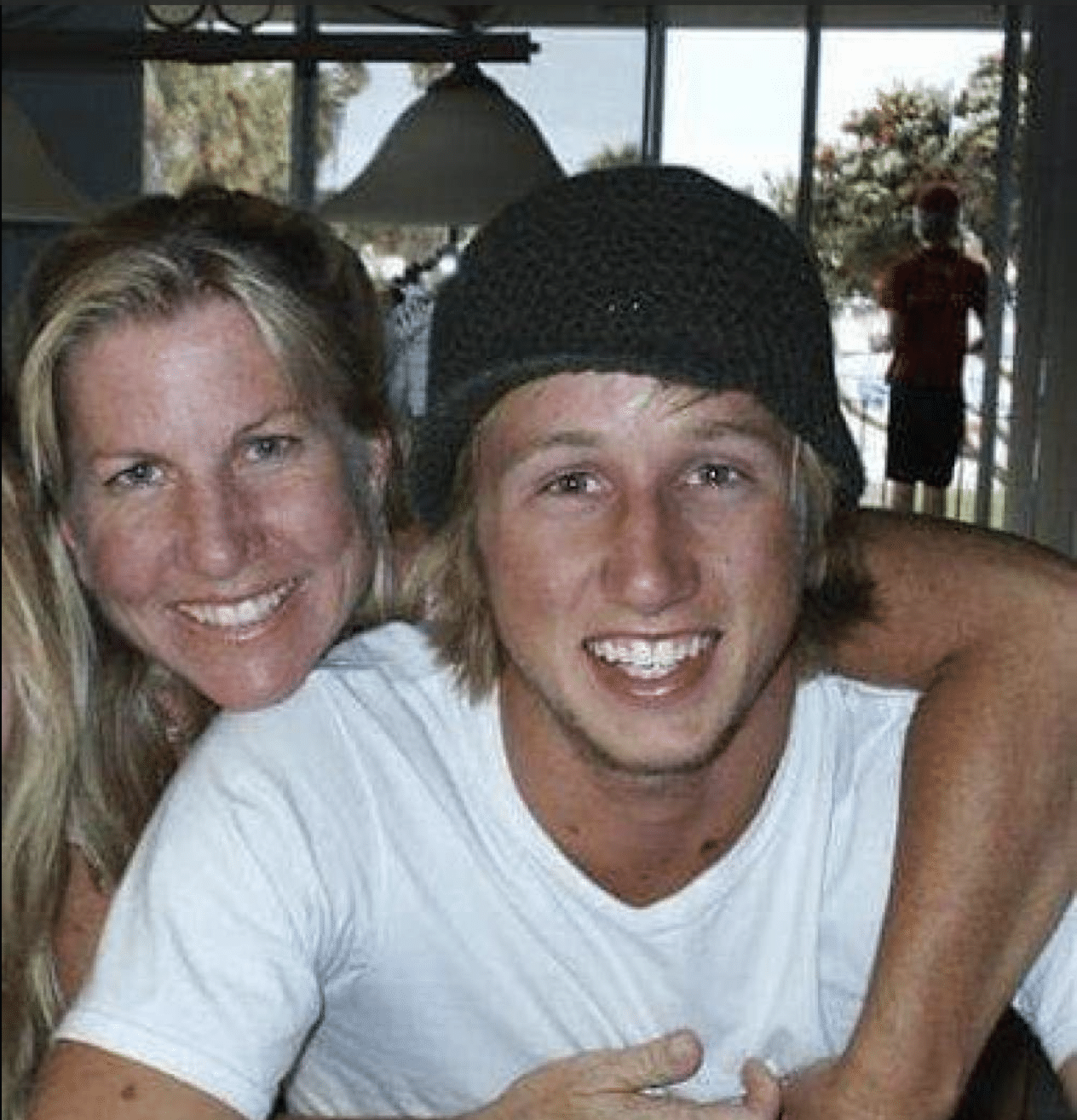

There aren’t many photos of Jonathan Chase Adams. “He didn’t like having his picture taken,” his younger sister Jessica says. “Neither do I. We’re the same like that.”

Adams grew up in Laguna Niguel, in Southern California, and attended community college in neighboring Mission Viejo. But eight years ago, Adams moved to Bend, Oregon; he wanted to be closer to family, and the great outdoors in the Bend region was a natural draw for him.

The morning of November 20, 2017, Adams was riding his bike to his job at Carl’s Jr. It was cold, and it had been raining lightly. Adams was traveling north in the bike lane on NW Wall Street. At 11:20, as he approached the intersection with NW Olney Ave, he was just a half mile from work. A couple of minutes and he’d be there.

Up ahead, at the intersection, there was a red light, and a line of vehicles that had stopped at the light. Adams began passing the line of vehicles as he approached the intersection. His timing was perfect—before he reached the intersection, the light changed to green, and traffic began moving forward again. Adams continued straight through the intersection.

He never made it to the other side.

As Adams entered the intersection, the vehicle to his left, a FedEx Ground semi-trailer truck hauling a 25 foot trailer, began making a right turn onto NW Olney Ave. Adams was struck by the side tank, and bounced several times into the side of the trailer, trying desperately to get away from the truck as it continued turning into him.

As Adams began to lose control of his bike, he put his left leg down; his leg was caught by a wheel, and he was dragged under the trailer, and then run over by the rear wheels. Adams, 31, died at the scene. It was three days from Thanksgiving.

His family later spoke about the son and brother they had lost that cold Thanksgiving week. His mother Janet described him as a gifted athlete with a soft spot for kids.

Janet Adams and her son Jonathan Chase Adams

His younger sister Jessica said her brother was her protector as far back as her earliest memories.

“He was the gentlest, warmest and most genuine person I know, she said. “He was 100 percent honest—to his core. I am very proud to have him as my big brother.”

Jonathan Chase Adams

A Tragedy Becomes a Travesty

In the immediate aftermath of the fatal collision, a narrative about what had happened began to take shape. In turn, that narrative later became courtroom testimony about what had happened.

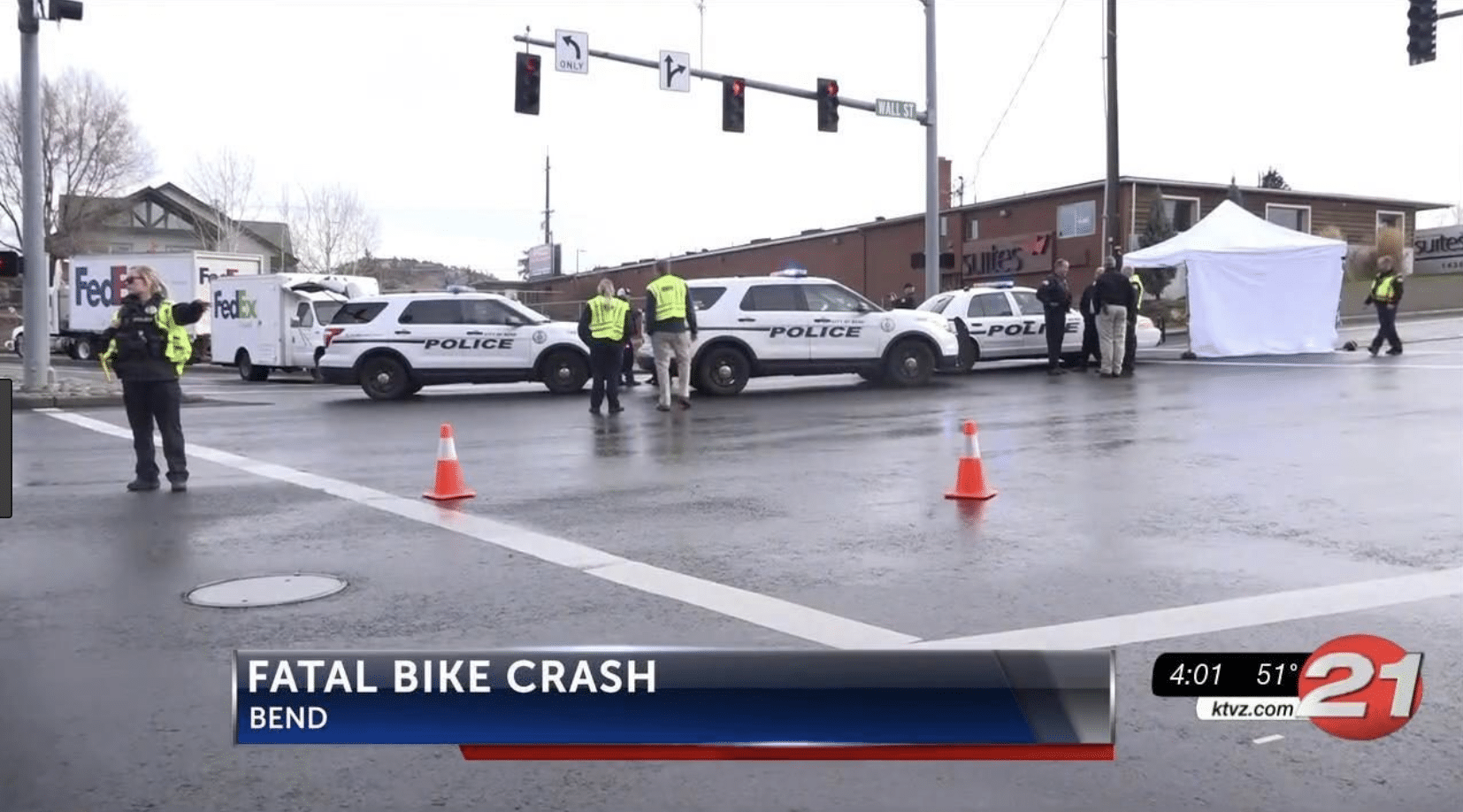

The scene of the fatal collision, looking east onto NW Olney Ave.

Police responding to the scene of the crash declined to ticket the FedEx driver. However, six months later Deschutes County District Attorney John Hummel announced that while he would not be filing a criminal charge against the driver, he would be charging the driver with a traffic violation, Failure to yield to rider on a bicycle lane.

In Oregon, this statute, in conjunction with certain exceptions outlined in a separate statute, means that cyclists in the bicycle lane have the right of way, and drivers who are making a turn across the bicycle lane must yield that right of way. And this means that because drivers are required to yield the right of way, they have a legal duty to carefully look for cyclists before crossing the bike lane.

The driver could have paid the fine on the citation, but because a conviction on the traffic citation would negatively impact his commercial driver’s license, the driver chose to fight the citation in court. That decision, in turn, had the potential to affect a wrongful death lawsuit filed by Chase’s family. A trial date was set for October 15, 2018.

At trial, testimony revealed that the FedEx driver had been stopped at the intersection, with about 10 cars ahead of him waiting at the red light. The driver had his turn signal on as he waited, preparing to turn right when he reached the intersection.

Adams was riding in the same direction as the FedEx truck, in a bike lane next to the line of stopped cars. Testimony indicated that Adams was not wearing a helmet, reflective clothing, or a light.

David Robertson, a Battalion Chief with the U.S. Forest Service, was driving the car directly behind the FedEx truck, and testified in court about what he had witnessed. Adams, he said, had been “bombing” down the hill towards the intersection, and as the FedEx truck began turning into Adams,

“I started screaming, ‘No! No! No!’ but my window was up,” Robertson said. “You know, it’s November and it’s cold out.”

Adams himself was unable to provide his own testimony, so the court never heard his account of what had happened. But I’ll take the liberty of saying a few words in his defense.

First, about that helmet Adams was not wearing—so what? It’s perfectly legal for anybody 16 or older to ride a bike in Oregon without a helmet. And in fact, Oregon law prohibits the lack of a helmet from being introduced as evidence in a civil suit regardless of the age of the cyclist. The reason the law prohibits introducing the cyclist’s lack of a helmet into evidence is because arguing that “the cyclist wasn’t wearing a helmet” only serves as a pretense for shifting the blame away from the careless driver and onto the careless driver’s victim. It’s a way of saying “if you weren’t wearing a helmet, don’t blame the careless driver for the injuries you received.” And the Oregon legislature has made it clear that this “blame the victim” defense will not fly in Oregon courtrooms.

And yet, that’s exactly what was happening to Jonathan Adams when testimony revealed that he wasn’t wearing a helmet—and this victim-blaming was happening specifically because the trial was a prosecution of a traffic violation, rather than a civil suit, where the victim-blaming would be prohibited. So was this victim-blaming in any way relevant to the defense on the traffic violation? Absolutely not. It’s as relevant as asking if the driver was wearing a helmet. And we all know that didn’t happen. It was just a way to say “Look, over there! Shiny squirrel!”

And Judge A. Michael Adler allowed it.

As if that’s not bad enough, remember, Jonathan Adams was run over by the rear wheels of a semi-trailer truck. A bicycle helmet would not have saved his life. In fact, bicycle helmets aren’t designed to prevent injuries in anything more serious than a low-speed fall from a four-to-six foot height—the kind of fall that would happen if you simply fell off your bike at low speed and hit your head on the pavement. They’re not designed to prevent injury if a semi-truck rolls over your head, and they’re certainly not designed to prevent internal injuries if a semi-truck rolls over your torso. So there’s not even any valid safety reason to admit the lack of a helmet into evidence. It’s just a “Shiny squirrel!”

Another shiny squirrel was pointed out when testimony revealed that Adams was not wearing reflective clothing or a light. Again—so what? It was broad daylight. There’s no requirement in Oregon law for either reflective clothing or a light in broad daylight—just like there’s no requirement in Oregon for the FedEx driver to be wearing reflective clothing or a light.

One could argue that reflective clothing might have made Adams more visible, but that would only be true if it was nighttime and Adams was directly in front of the driver, and the driver had his lights on and directed at Adams. To the driver’s side, where Adams actually was, reflective clothing would have made no difference at all.

Well, what about hi-viz clothing? Again, it’s not required by Oregon law, but even if Adams had been wearing hi-viz clothing, it couldn’t possibly help the driver see him unless the driver was actually looking for approaching cyclists. And as we’ve seen time and time again, even when a cyclist is wearing reflective or hi-viz clothing, or riding with lights, police will still go to great lengths to let the driver off the hook.

When a careless driver right-hooked Siobhan Doyle in Portland, police did nothing, even though Doyle was wearing a long-sleeve fluorescent yellow jacket when the driver passed Doyle before making a right turn into Doyle. The driver was only brought to justice through a citizen-initiated citation—a remedy unique to Oregon law, through which a private citizen can issue a traffic citation.

Similarly, when Chattanooga cyclist David Meek was hit by a truck driver who “never saw him,” he was “lit up like a Christmas tree,” and police nevertheless contorted themselves into backbends to exonerate the driver.

In Bend, testimony revealed that Jonathan Adams was not equipped with a light when the FedEx driver turned into him. While a light may have helped the FedEx driver see Adams approaching from behind, it wasn’t required by law, and it could only help the driver see Adams if the driver was actually looking for cyclists before turning.

And that’s the important thing to understand about Oregon law—when a driver is making a turn across a bike lane, the driver has a legal duty to yield the right of way to a cyclist who is in the bike lane. Oregon law doesn’t say “yield if you see a cyclist.” It says the law is violated if the driver “does not yield.” That language puts the onus on the driver to look carefully for cyclists in the bike lane before turning across the lane. You turned without looking? You’re at fault. You gave a quick, cursory look, and didn’t see the cyclist? You’re still at fault. You stopped before turning, looked carefully, didn’t see a cyclist, but there was nevertheless a cyclist in the bike lane and you collided? Now we can try to figure out if you or the cyclist are at fault.

To see how this works, we can compare Oregon law with California law. In California, drivers are required to merge carefully with the bike lane before making a right turn. This language puts the onus on the driver to observe for cyclists before merging; to simply merge without doing so carefully would be illegal in California.

Oregon takes a different approach. In Oregon, drivers are not permitted to operate in the bike lane. Instead, when making a right turn, drivers are required to yield to any cyclists in the bike lane. This requirement is identical to the requirement drivers have at a yield sign—a driver can only enter an intersection controlled by a yield sign when there is no cross-traffic with the right of way. There is nothing in the law that says “if the driver sees other traffic.” It says quite plainly that the driver has the duty to yield. As with bike lanes, this puts the onus for yielding squarely on the driver who does not have the right of way. In both instances, the only way to comply with the law is to carefully observe for the right of way before crossing.

So how did a FedEx driver fail to yield to Jonathan Adams while he was riding in the bike lane? There are only two possibilities– either he deliberately violated the cyclist’s right of way, which seems unlikely, or he violated the cyclist’s right of way because he didn’t see him. And if he didn’t see him, we have to ask why. It was broad daylight. Adams was in the bike lane. We know for a fact that he was visible in the driver’s rear-view mirror. He should have been visible in the driver’s side mirror. And the driver had a legal duty to look before turning. So why didn’t he see Adams?

The “shiny squirrel” defenses were an attempt to answer that question—by shifting the blame to Adams. He couldn’t be seen because he wasn’t wearing reflective gear, even though that would be totally irrelevant unless he was directly in the truck’s lights at night. It’s the kind of defense one might raise if one had made a cursory check, if at all, before turning. It’s not the kind of defense one would raise if one had carefully checked to make sure that the bike lane was clear before turning.

And we can deduce that the driver did not in fact look carefully before turning. How can we know this? The driver’s defense was not “I looked carefully and did not see a cyclist before beginning my turn.” Instead, the driver argued that there is no bike lane in the intersection, so he could not be in violation of the law requiring that he yield to Adams.

Think about it. If the driver had actually looked carefully before turning, wouldn’t that have been his argument? Why argue that there is no bike lane in the intersection, unless that is your best way of explaining what happened? Even if the driver couldn’t see Adams because he was in the driver’s blind spot—a difficult argument to make, given the side mirrors on FedEx trucks—wouldn’t that be the argument he would want to make? And in fact, evidence revealed that Adams was indeed visible in the driver’s rear-view mirror before they reached the intersection.

But if there was no bike lane, then the driver could argue that he did not violate the law when he made his right turn. And that was exactly the strategy chosen. In a 2009 case in Portland, a driver right-hooked Portland cyclist Carmen Piekarski at an intersection. The driver was cited by police for Failure to yield to rider on bicycle lane. But at trial, Judge Pro Tem Michael Zusman held that because there are no bike lane markings in the intersection, the bike lane does not continue through the intersection.

While Judge Zusman was basing his ruling on the statutory language, in which bicycle lanes are designated by signs or lane markings, his ruling was profoundly lacking in legal logic. If, as he held, bicycle lanes do not exist in intersections, then what would be the purpose of a law that requires drivers to yield the right of way before making a turn across a bicycle lane? Did he suppose that the law only applies to driveways adjacent to bike lanes? And if so, why would the legislature have seen fit to protect cyclists at driveways, but not in intersections?

To make matters worse, there was virtually no expert agreement with Judge Zusman’s reading of the law, from law enforcement, to legal experts, to ODOT. Nevertheless, even though the driver in this case was not found in violation of the bike lane statute, the case itself had no value as legally-binding precedent, because it was a trial-level ruling, rather than an appellate ruling, and applied only to that specific case. Piekarski, who suffered injuries including serious road rash and a shoulder injury, eventually settled out of court with the driver’s insurance company.

While it was clear to almost everybody that the ruling in this case was an aberration, Jonathan Maus at Bikeportland made the now-prescient observation that “the law itself could use a bit of clarification so this doesn’t happen again.”

And now, nine years later, it was happening again—only this time, a right-hook in an intersection had taken a cyclist’s life. And this time, the driver was basing his argument on Judge Zusman’s ruling. And like Judge Zusman, Judge Adler saw “no authority” for the argument that bike lanes continue through intersections—despite Prosecutor Andrew Steiner’s introduction into evidence of “Oregon Department of Transportation guidelines for road construction standards and recent court cases and legislation in Oregon.” Facts were simply no match for logic-defying myopia.

But perhaps recognizing that Judge Zusman’s ruling needed some additional buttressing, Judge Adler came up with his own contribution to the “disappearing bike lanes” legal canon: Adams’s “speed carried him outside the protection of the bike lane.” Because testimony had been presented that Adams had been “bombing” down the hill toward an intersection, and past a truck with its turn signals on, Judge Adler ruled that Adams had not been exercising “due care.” What Judge Adler appeared to be saying was that Adams had a duty to slow and yield to the truck before entering the intersection, and that because he didn’t slow and yield, he was in the intersection, and not in the bike lane, at the precise moment that the truck began to turn.

Picture this: You’re driving your car in the right lane. As you enter an intersection, the car in the left lane next to you makes a right turn across your lane, cutting you off, and you collide. According to Judge Adler, you didn’t yield the right of way to the other vehicle, and because there was no lane in the intersection, your right of way was not violated. You should have slowed and yielded to the car making a turn across your lane, and because you were in the intersection, you were “outside the protection” of your lane.

If this seems wrong to you, it’s because it is wrong. There’s no such rule in the law. Even if you’re driving a little faster than the car in the lane next to you, they still have a duty to make a safe turn, or a safe lane change, and they still don’t get to violate your right of way.

And was Adams really “speeding”? The posted speed limit is 20 MPH on that stretch of road, and the “hill” he was “bombing” down is a slight grade.

NW Wall Street, looking south. Jonathan Adams was riding in the same direction as the cars in this photo when he was right-hooked at this intersection.

NW Wall Street, looking south. Jonathan Adams was riding in the same direction as the cars in this photo when he was right-hooked at this intersection.

It’s not uncommon in right-of-way violations for the blame to be shifted to cyclists because it’s alleged they were “speeding.” In 2007, when Portland cyclist Brett Jarolimek was right-hooked and killed on a downhill grade, the District Attorney’s report revealed that Jarolimek was traveling at approximately 22-28 MPH on a 7.5% grade with a 30 MPH speed limit. Despite the truck having a defective mirror, Jarolimek’s speed was identified as a factor in the collision. Similarly, when Lloyd Clarke was killed in Incline Village by a teen driver who turned left across his right of way, police shifted the blame to Clarke, citing his speed on an 8 or 9% grade.

It’s unclear how fast Adams was traveling that morning, but the relatively shallow grade makes it unlikely that he was traveling much faster than the 20 MPH speed limit, and the fact that the vehicles in the traffic lane were stopped at a light as he passed them as has likely contributed to the impression that he was “bombing” down the hill. In fact, for all we know, he was traveling within the speed limit when he was right-hooked.

No matter. This wasn’t really about the law. The problem, as Prosecutor Andrew Steiner noted, is that people don’t understand that bicycle lanes are vehicle lanes. “This is cultural,” he said. “Many people just don’t think of them as lanes.”

The District Attorney’s office did everything they could to bring justice to this tragedy. The prosecutors understood the law, and the facts, and did everything they could, only to be shut down in court by a law that doesn’t exist. It was out of their hands now. There was only one way left to ensure that no future cyclist would be denied justice in a court of law. The legislature would have to step in and tell judges in plain English what everybody else has been trying to explain to them with no avail.

Righting a Wrong: A New Law

What happened to Jonathan Chase Adams that cold November morning in 2017 was a tragedy, in every sense of the word. But what happened at trial was a travesty. And the legislature may finally be stepping in to set Judges straight on what the law means. On April 15th, a House Bill clarifying that bike lanes do in fact continue through intersections passed the Joint Committee on Transportation. The bill then went to the House, where it passed by a wide margin on April 25. On Monday, April 29, the bill will have its first reading in the state Senate.

Judges Zusman and Adler sent the message to Oregon drivers that they don’t have to look for or yield the right of way to cyclists in intersections. If the Bike Lane bill becomes law, the legislature will send a different message to drivers: you have a duty to watch for and yield to cyclists when you make a turn in an intersection.

If you’ve been in a bike crash and need help from our Oregon bicycle accident attorneys, contact us right away.