Reflections on the Asian-American experience and why we are so honored to sponsor Clarice.

Bike Month 2021 is setting the bar pretty high. Two days ago, Sika Henry became the first Black woman to earn her pro card in the sport of triathlon. And today, Bike Law and I are honored and excited to announce our sponsorship of the only Asian-American racing on the professional triathlon circuit, Clarice Chastang Lorenzini.

Clarice, the 27 year old US-born daughter of a Filipino immigrant mother and a French immigrant father, recently qualified for her elite license (”pro card”) last November 2020 at Ironman Florida. She races on weekends, trains in the mornings and evenings, and during the week, works to provide recreational programming and sober leisure education to military personnel battling addiction. Her husband is an active-duty sailor in the Navy and she says that “his dedication to our country inspired me to give back to those who serve.”

Clarice is also a triathlon coach with Speed Sherpa, a coaching service and inclusive racing team that has long since been aligned with Bike Law in its compassionate and responsible community ethos, mission, and practices.

Our Stories Are The Same

Bike Law believes in Clarice, and her story resonates with me especially. I feel it is important to share with all Americans regardless of whether or not they ride a bike or participate in competitive sport. For those of us who do, Clarice’s recent step up into the pro field of a sport that has long struggled with equity and accessibility helps to create the necessary space for more diverse participation. Her representation opens that door — almost for the first time (she is only the second Asian-American to qualify for her pro card in triathlon history) — and Bike Law and I are thrilled to support her in hopes that other Asian-American girls and women and People of Color will feel more welcomed, confident, and comfortable joining a community where previously they may have felt excluded and alone.

Like me, Clarice spent her childhood stuck between her roots and her branches, trying to balance the universal challenges of American adolescence with her undisguisable differences and Asian heritage.

“For a majority of my childhood I rejected my mother’s (and, well, my) culture. I was ashamed to be Asian. I would argue with my mom that I was American, not Asian, and wanted to be treated like my Red, White, and Blue peers. She was unaware of the criticism I received in school, at social events, and while playing with other kids- all of which made me resent her and who I was.”

“I was mocked for the majority of my childhood, making me suppress the culture my mother worked so hard to preserve and instill. Other children would mock my Asian eyes, the way my skin resembled my mother’s skin color, and so much more. They would call me ‘dirty,’ pull & stretch their own eyes to the side, call me names, and ask if I could even see with eyes that weren’t the same rounded shape as theirs. In school, during recess and gym, students would continue making fun of me by saying things like, “If we tag Clarice she won’t even know because her eyes are closed!””

At 27, and in light of our country’s recent broadened exposure to previously ignored current events and injustices, Clarice is not only strong and settled in her Asian roots, but is embracing those once rejected native gifts bestowed upon her by her immigrant Filipino mother as important parts of the woman and athlete she is today. She is no less American than the kids who taunted and teased her- the ones she so desperately wanted to be like (or look like?). And Clarice won’t let this opportunity to address, for others, some of the devaluing hurt and discrimination that she experienced to pass her by.

She asserts with a smile that, “I am here to make a difference, and I’m not going anywhere.”

Clarice and Her Mom

Clarice’s experiences are all too familiar to me, my family, and my Asian-American friends. The blatantly discriminatory treatment she received is the rule, not the exception for Asian Americans who have long been pigeon-holed into “U.S.minority-limbo”- an embarrassing and shameful indictment that doesn’t only harm those of us whose citizenship is defined differently than any other minority group, but also continues to perpetuate a culture of inequity and exclusion for other diverse Americans.

Asian-Americans & The Myth of the Model Minority

No one knows just what to think about or do with us. In some places we’ve set the bar too high. There are actual consequences for being Asian (or “too Asian”). For example, some prestigious Ivy League universities have implemented a pattern and practice in which race and religion are metrics used by admissions officers to determine a potential student’s eligibility. However, unlike affirmative action which is designed to diversify, these quotas literally aim to limit the number of Asian students at such schools because “too many” of us create both an academic and PR imbalance that appear to risk the exclusion of applicants of ALL other races.

The odds against Asian-American students for admission into highly selective colleges and universities are greater by a factor of 3, 6, and 16 than their White, Hispanic, and Black peers. This practice is one of the worst in the history of American higher education, and as it continues today, it is, in my opinion, more damaging than we’re willing to acknowledge because it inarguably escalates tensions between minority groups while marginalizing them as well. (If Asian Americans can pull ourselves up from our bootstraps, why can’t everyone else?”) It’s a practice that undermines two of the most important and fundamental American principles: meritocracy and equality.

Yes, those two things CAN co-exist. And the path to both begins with education, advocacy, and opportunity.

“Model Minority” (Asian-American) children have been unfairly and inhumanely identified by complete strangers as being “quiet, shy, rigid, math-oriented, and hard-working.” No matter how long we’ve lived here, we’ll always be identified as foreigners. We’re all familiar with the racial epithet used to describe mothers of Asian descent who demand unachievable excellence (perfection) from their children, usually resulting in emotionally stunted but highly functioning engineers, doctors, mathematicians, and scientists.

Since having children of my own, I’ve been called a “Tiger Mom” more times than I can count. (If you’ve met my boys, you’d testify that they’re neither stunted nor likely to split the atom, but they do live normal (for Asian American bi-racial kids in the Southeast), well-adjusted lives. And if you know me personally, then you’re probably thinking that I’d value and prioritize education, integrity, work ethic, family, and altruism exactly the same way, whether I was born in Seoul or San Antonio.)

Skin In The Game (Yes, It’s Personal)

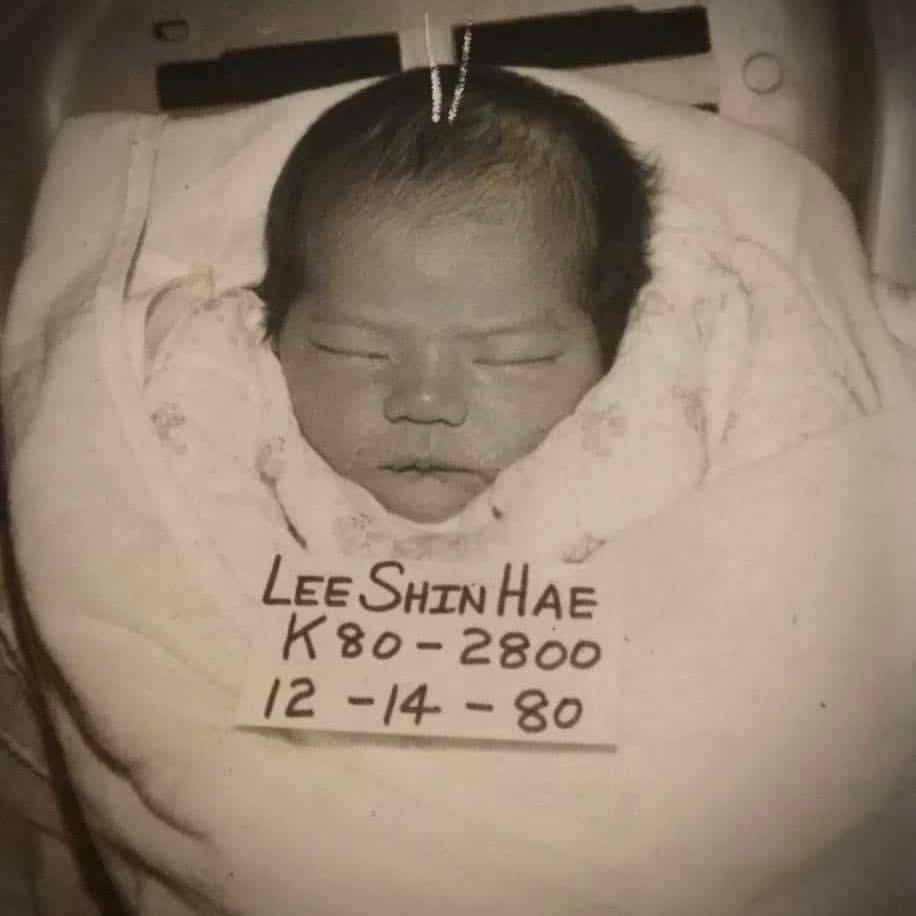

I’m Korean adopted.

Born in Korea . . .

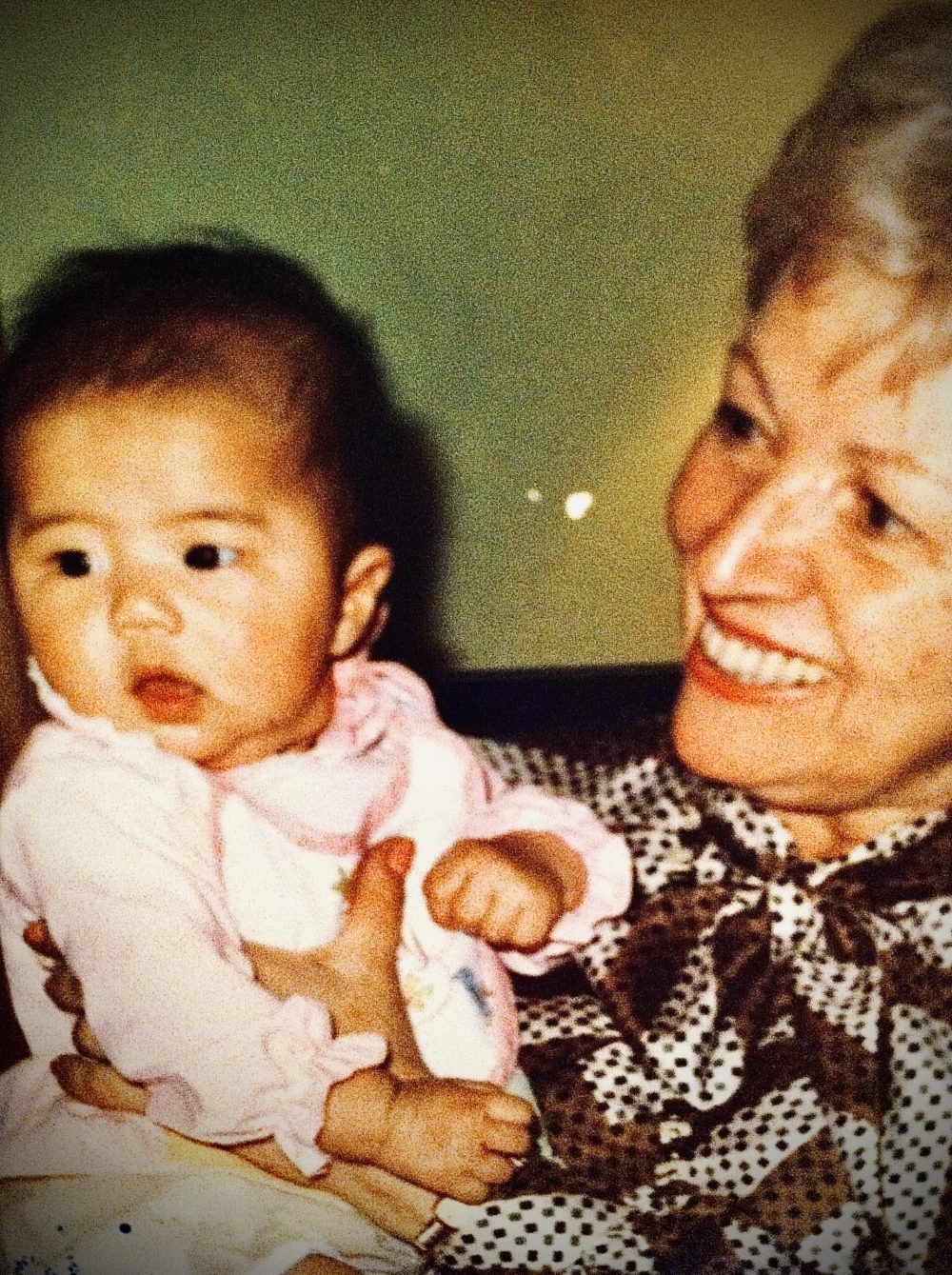

I’m also half Jewish. My father is a first generation Austrian Jew whose parents fled Europe during the Holocaust. My mother is of Polish-Hungarian descent and was the second person in her family to be born on U.S. soil. Growing up, my paternal grandmother was a powerful driving force in my life. She taught me the most valuable life lessons, and it’s her experiences and resilience that are largely responsible for who I am today. One of the things that being so close to her revealed to me is that the way Americans treated Jewish immigrants during the early and mid 1900s parallels (with striking similarities) the discriminatory treatment of Asian Americans today.

Loved by my Austrian Grandmother (and Holocaust Survivor) in the USA.

And like Clarice, I have not spoken about the experiences I had growing up (or the ones since becoming a mother) that made me wish, albeit in silence, that I looked more like my classmates, teammates, and neighborhood playmates. I didn’t actually want curly, blonde hair or blue eyes when I begged my mom for Sun-in, a perm, and colored contacts (and thank goodness she told me “No!”). I just wanted to blend in.

I wanted to belong.

And as an Asian American adoptee who looked nothing like my peers OR parents, it took me a little longer to figure out how my roots connected to my branches.

These themes are the underpinning of multi-faceted and systemic inequity. These occurrences are far too normative; they are hurtful and undermine the most basic and universal human need: to feel accepted and comfortable being exactly who we are.

These inequities exist not only on school and college campuses but in American offices, strip malls, transportation, politics, religion, science…and sport.

Why? Well, my observations and experiences have led me to understand that [we] Americans struggle to embrace a worldview that has room for more than 2 choices, even though the rest of the world has moved on from restrictive and outdated binary living, or at least they are trying.

We don’t seem to get it. We want all the features of diversity, but then we label them as bugs.

We’re In It To Win It (We’re In It To Change It)

Clarice has shared countless other examples of the ways her existence is criticized, exploited, and misused as an invitation to make comments that would no sooner be accepted by any other sub-group of people than it should be by her. And perhaps that’s where my life and Clarice’s, our experiences, and our personal and professional missions intersect. She told me that unlike the classroom, playground, and professional settings in which her peers and colleagues make jokes about what and how she eats, the shape of her eyes, how well she can (or cannot) see, and in the context of current events, the origin and impact of the “China Virus” and “Kung Flu,” the saddle and the race course provide a space to level things out so that each person in the field is no different than her: “a human, a dreamer, someone doing their best, just reaching for their goals.”

By speaking up and embracing her identity and heritage as an Asian-American woman in sport, my hope, and hers, is that Clarice can use her platform to show other Asian-Americans and people from diverse backgrounds and circumstances that they are enough, and they are not alone.

Our goal is to create doors, open them, reach out a hand to someone else, and step through together to the other side. Our shared vision is one of scalable growth and inclusion. We are prepared to open ourselves up and have difficult conversations. We want to educate and empower, not avoid, objectify, polarize, and divide.

We share the same belief that there is a bigger problem plaguing triathlon causing its relatively one-dimensional community. Clarice has identified its lack of accessibility. One of the many symptoms of this “velvet-rope” sport is that Clarice IS alone as the only Asian American professional racing on the circuit. And while her earned accomplishment is cause for celebration and recognition, it’s also a double-edged sword.

No one wants to be tokenized, and certainly not in 2021. As a woman who trains and competes without any performance advantage or disadvantage because she has beautiful almond shaped eyes like her Filipino mother, Clarice has found greater meaning and opportunity in her platform as a pro.

She says, “Recent events have inspired me to use my new platform as a professional triathlete to be an advocate. I speak about my life experiences so others can learn and understand the challenges that led me (and others like me) here. My goal is to maintain an ongoing conversation about race, equity, and breaking cultural and socioeconomic barriers so that triathlon becomes a more inclusive and diverse sport. With a lot of hard work ahead, maybe one day we’ll reach that young Asian girl who can see the work we’ve accomplished and break through that cultural barrier to reach her dreams; whether they are athletic, academic, or something we haven’t even considered.”

I am proud of my roots. I am proud of my branches. I am proud to be Korean-American. I was proud to race for Team USA.

USA, USA, USA!

And I am proud to welcome Clarice Chastang Lorenzini to the Bike Law family. Our full sponsorship is representative of our commitment to change and our stance in solidarity with her, the Asian American community, and with all people who have been told “Yes” or “No” because of characteristics that are different, beautiful, and completely outside of their control.

Today, all Bike Month long, and every day after, Bike Law is committed to seeing, hearing, and advocating for each and every one of you. We invite and encourage you to join us, and like Clarice asked so confidently of me:

“Let’s change the face of this sport together.”

In the saddle or out,

No matter how, when, where, or why you ride,

We’re always on your left, protecting your rights.

Rachael Maney is the Director of the Bike Law Network and of the non-profit Bike Law Foundation.