Bike lanes continue through the intersection, even if they are not painted onto the roadway, and drivers who don’t yield to a cyclist riding in a bike lane are violating the law.

The big bike news out of the Oregon legislature this year was the passage of a Stop as Yield law. This was an enormous legislative victory for Oregon cyclists, the culmination of over a decade of advocacy.

But it wasn’t the only legislative victory for Oregon cyclists this legislative session. A less glamorous but equally important addition to Oregon’s bike laws was the passage of a bill clarifying that bike lanes continue through intersections.

Sounds kind of boring, doesn’t it?

It’s not. It’s a tale of heartbreaking tragedy, stunning displays of judicial illogic, and justice not only delayed, but flat out denied. And finally, it’s a tale of the triumph of law and reason over prejudice masquerading as logic and law.

.

And it all began with a simple question: Does a bike lane continue through an intersection?

There’s a simple way to understand the question. Have you ever heard that it’s illegal to change lanes in an intersection? It’s a common, but erroneous belief. It’s not illegal in Oregon, or in any of the surrounding states. It is widely considered to be an unsafe practice, and a driver can be ticketed for making an unsafe lane change in an intersection. But illegal? Nope.

On one level, this belief is just a mistaken understanding about the law. But on another level, it reflects a deeper understanding about intersections that is true—lanes continue across intersections, even though they’re not actually painted on the road surface. And because you can be ticketed for making an unsafe lane change when you are in an intersection, it should be obvious that even though the lanes aren’t painted across the intersection, they’re still there.

It’s common sense, really, and it’s also the official position of ODOT. Virtually everybody gets that.

And then there’s Judge Pro Tem Michael Zusman.

In a 2009 case in Portland, a driver right-hooked Portland cyclist Carmen Piekarski at an intersection. The driver was cited by police for Failure to yield to rider on bicycle lane. But at trial, Judge Zusman held that because there are no bike lane markings in the intersection, the bike lane does not continue through the intersection.

Put simply, Judge Zusman’s ruling was profoundly lacking in legal logic. If, as he held, bicycle lanes do not exist in intersections, then what would be the purpose of a law that requires drivers to yield the right of way before making a turn across a bicycle lane? Did he suppose that the law only applies to driveways adjacent to bike lanes? And if so, why would the legislature have seen fit to protect cyclists at driveways, but not in intersections?

To make matters worse, there was virtually no expert agreement with Judge Zusman’s reading of the law, from law enforcement, to legal experts, to ODOT. Nevertheless, even though the driver in this case was not found in violation of the bike lane statute, the case itself had no value as legally-binding precedent, because it was a trial-level ruling, rather than an appellate ruling, and applied only to that specific case. Piekarski, who suffered injuries including serious road rash and a shoulder injury, eventually settled out of court with the driver’s insurance company.

If there was any consolation to be had from Judge Zuman’s confused interpretation of the law, it was that this was a one-off aberration, never to be repeated. Still, Jonathan Maus at BikePortland made the now-prescient observation that “the law itself could use a bit of clarification so this doesn’t happen again.”

Time passed, and the law was never clarified. With every passing year, Judge Zusman’s ruling receded further into the past, a distant, half-forgotten clusterfudge of jurisprudence.

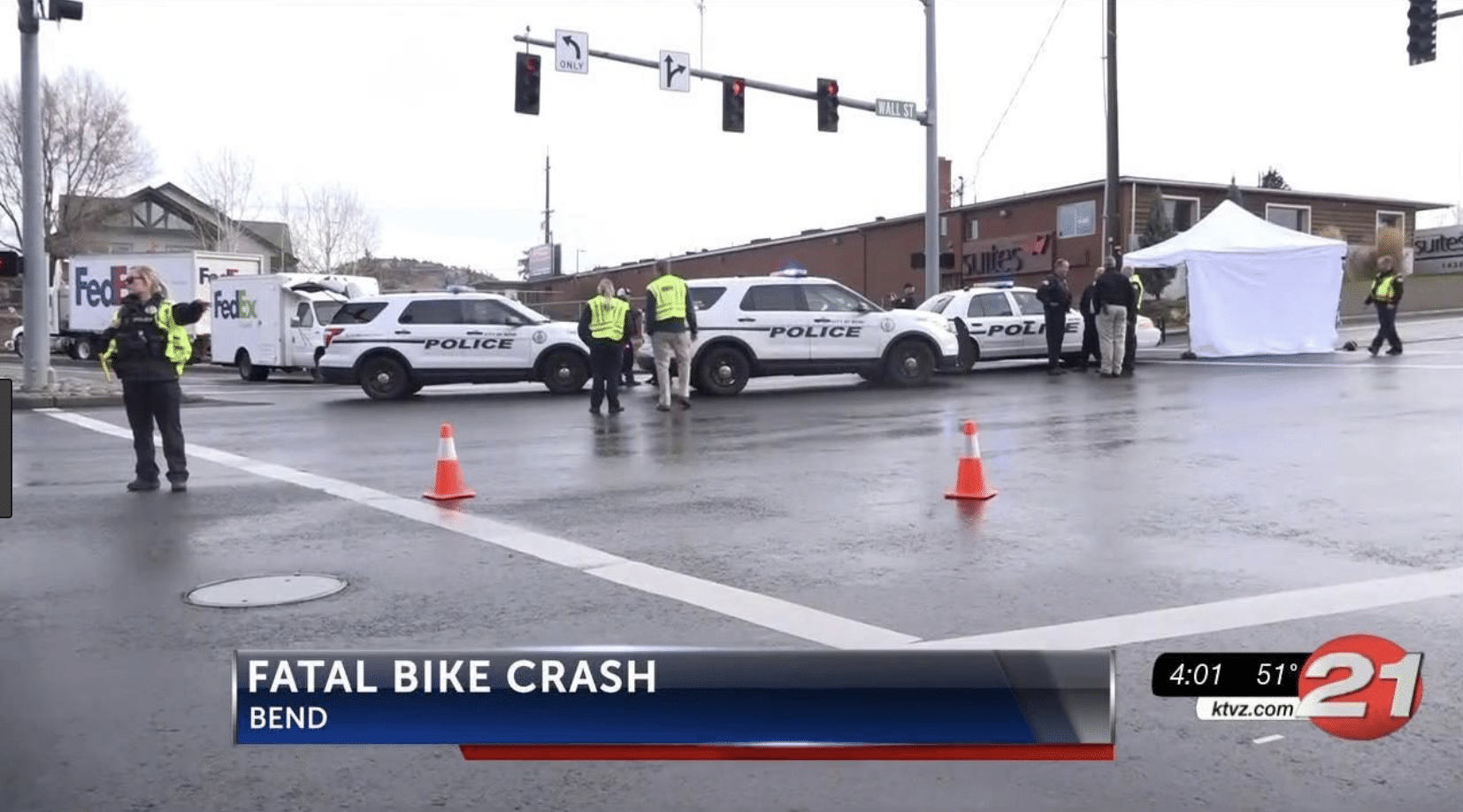

And then, on November 20, 2017, Jonathan Chase Adams rode his bike into a Bend, Oregon intersection.

He never made it to the other side.

As Adams entered the intersection, the vehicle to his left, a FedEx Ground semi-trailer truck hauling a 25 foot trailer, began making a right turn onto NW Olney Ave. Adams was struck by the side tank, and bounced several times into the side of the trailer, trying desperately to get away from the truck as it continued turning into him.

Adams began to lose control of his bike, and he put his left leg down; his leg was caught by a wheel, and he was dragged under the trailer, and then run over by the rear wheels. Adams, 31, died at the scene. It was three days from Thanksgiving.

Police responding to the scene of the crash declined to ticket the FedEx driver. However, six months later Deschutes County District Attorney John Hummel announced that while he would not be filing a criminal charge against the driver, he would be charging the driver with a traffic violation, Failure to yield to rider on a bicycle lane.

Fearing the loss of his commercial driver’s license if he paid the citation, the driver decided to fight the ticket. And once in court, the defense turned the tables and put Jonathan Chase Adams on trial. He had been “bombing” down the hill towards the intersection. He wasn’t wearing a helmet. He wasn’t wearing reflective clothing. He wasn’t equipped with a light.

These were all issues raised to distract from what had actually happened, to shift the blame to the cyclist by painting him as a danger to himself, and to absolve the driver of any responsibility for the fatal collision. And as is usually the case, the cyclist wasn’t able to tell his own story.

He wasn’t wearing a helmet—but a helmet would not have prevented the tires of the truck from running over him after he was dragged under, and it wouldn’t have protected his body or his head from the injuries he suffered.

He wasn’t wearing reflective clothing. But it was broad daylight, reflective clothing wasn’t required, and it wouldn’t have made a bit of difference.

He wasn’t equipped with a light, but again, it was broad daylight. There was no excuse for why he couldn’t be seen.

He was “bombing” down the hill, but no actual evidence was introduced to establish his speed. Instead, the court heard the perceptions of drivers who had been sitting still in traffic as Adams passed them. And more to the point, he was adjacent to the cab of the truck as both the truck and Adams entered the intersection. When the truck right-hooked him, Adams was struck by the side tank of the cab.

This means that the driver should have seen him in the side mirrors. Had the driver been looking for cyclists as he turned across the bike lane, as Oregon law requires, he would have seen Adams. In Oregon, when a driver is making a turn across a bike lane, the driver has a legal duty to yield the right of way to a cyclist who is in the bike lane. Oregon law doesn’t say “yield if you see a cyclist.” It says the law is violated if the driver “does not yield.” That language puts the onus on the driver to look carefully for cyclists in the bike lane before turning across the lane. You turned without looking? You’re at fault. You gave a quick, cursory look, and didn’t see the cyclist? You’re still at fault. You stopped before turning, looked carefully, didn’t see a cyclist, but there was nevertheless a cyclist in the bike lane and you collided? Now we can try to figure out if you or the cyclist are at fault.

So how did a FedEx driver fail to yield to Jonathan Adams while he was riding in the bike lane? There are only two possibilities– either he deliberately violated the cyclist’s right of way, which seems unlikely, or he violated the cyclist’s right of way because he didn’t see him. And if he didn’t see him, we have to ask why. It was broad daylight. Adams was in the bike lane. We know for a fact that he was visible in the driver’s rear-view mirror. He should have been visible in the driver’s side mirror. And the driver had a legal duty to look before turning. So why didn’t he see Adams?

The defenses the driver raised—helmet, lights, clothing, “bombing” down the hill—were an attempt to answer that question, by shifting the blame to Adams. He couldn’t be seen because he didn’t have a light (in broad daylight). He couldn’t be seen because he wasn’t wearing reflective clothing (in broad daylight). He couldn’t be seen because he was “bombing” down a hill (past drivers who were stuck sitting still in traffic). He couldn’t be seen because he wasn’t wearing a helmet—no, that doesn’t make sense, but mention the missing helmet anyway, it makes him look negligent.

It’s the kind of defense one might raise if one had made a cursory check, if at all, before turning. It’s not the kind of defense one would raise if one had carefully checked to make sure that the bike lane was clear before turning.

And we can deduce that the driver did not in fact look carefully before turning. How can we know this? The driver’s defense was not “I looked carefully and did not see a cyclist before beginning my turn.” Instead, the driver argued that there is no bike lane in the intersection, so he could not be in violation of the law requiring that he yield to Adams.

Think about it. If the driver had actually looked carefully before turning, wouldn’t that have been his argument? Why argue that there is no bike lane in the intersection, unless that is your best way of explaining what happened? Even if the driver couldn’t see Adams because he was in the driver’s blind spot—a difficult argument to make, given the side mirrors on FedEx trucks—wouldn’t that be the argument he would want to make? And in fact, evidence revealed that Adams was indeed visible in the driver’s rear-view mirror before they reached the intersection.

But if there was no bike lane, then the driver could argue that he did not violate the law when he made his right turn. And that was exactly the strategy chosen. Judge Zusman’s ruling was rising like a zombie from the grave of judicial error, just in time for Halloween.

And Judge A. Michael Adler bought it, hook, line, and sinker.

Like Judge Zusman, Judge Adler saw “no authority” for the argument that bike lanes continue through intersections—despite Prosecutor Andrew Steiner’s introduction into evidence of “Oregon Department of Transportation guidelines for road construction standards and recent court cases and legislation in Oregon.” Facts were simply no match for logic-defying myopia.

But perhaps recognizing that Judge Zusman’s ruling needed some additional buttressing, Judge Adler came up with his own contribution to the “disappearing bike lanes” legal canon: Adams’s “speed carried him outside the protection of the bike lane.” Because testimony had been presented that Adams had been “bombing” down the hill toward an intersection, and past a truck with its turn signals on, Judge Adler ruled that Adams had not been exercising “due care.” What Judge Adler appeared to be saying was that Adams had a duty to slow and yield to the truck before entering the intersection, and that because he didn’t slow and yield, he was in the intersection, and not in the bike lane, at the precise moment that the truck began to turn.

Picture this: You’re driving your car in the right lane. As you enter an intersection, the car in the left lane next to you makes a right turn across your lane, cutting you off, and you collide. According to Judge Adler, you didn’t yield the right of way to the other vehicle, and because there was no lane in the intersection, your right of way was not violated. You should have slowed and yielded to the car making a turn across your lane, and because you were in the intersection, you were “outside the protection” of your lane.

If this seems wrong to you, it’s because it is wrong. There’s no such rule in the law. Even if you’re driving a little faster than the car in the lane next to you, they still have a duty to make a safe turn, or a safe lane change, and they still don’t get to violate your right of way.

But not in Judge Adler’s courtroom. There, the driver turning across your path of travel has no duty to yield, or even to look before turning. The message to drivers throughout the state was unmistakable: Oregon drivers don’t have to look for or yield the right of way to cyclists in intersections.

The problem, as Prosecutor Andrew Steiner noted, is that people don’t understand that bicycle lanes are vehicle lanes. “This is cultural,” he said. “Many people just don’t think of them as lanes.”

The District Attorney’s office did everything they could to bring justice to this tragedy. The prosecutors understood the law, and the facts, and did everything they could, only to be shut down in court by a law that doesn’t exist. It was out of their hands now. There was only one way left to ensure that no future cyclist would be denied justice in a court of law. The legislature would have to step in and tell judges in plain English what everybody else has been trying to explain to them with no avail.

And that is exactly what happened. In May, the Oregon Legislature made clear what everybody had already been telling Judges Zusman and Adler: Bike lanes continue through the intersection, even if they are not painted onto the roadway, and drivers who don’t yield to a cyclist riding in a bike lane are violating the law.

This is an enormous legal victory for cyclists—not as glamorous, perhaps, as the passage of the Stop as Yield law, but a tremendous victory for justice nevertheless.

If you’ve been in a bike crash and need help from our Oregon bicycle accident lawyers, contact us right away.